Why Animal-Sourced Protein is Superior to Plant-Based Protein

While many foods contain protein, as amino acids, not all sources of protein are created equal.

Certain types of protein, particularly from animals, are a much better source of essential amino acids and overall nutrition when compared to plant-based proteins.

Protein is made up of amino acids (AAs). There are twenty AAs that our bodies utilize, nine of which are essential, meaning that our bodies must obtain these from food. (By contrast, a “nonessential” nutrient doesn’t mean we don’t need it; it simply means that our bodies can make it from the building blocks in other nutrients, so we don’t require it directly from our diets. That being said, conversion can be a difficult process, so consuming the true form is always preferred.) Animal products contain all the AAs we need, while plants lack one or more AAs, particularly leucine, which is one of the most important AAs for humans. So when a package of food lists “grams of protein,” it doesn’t really give you the full story on the spectrum of amino acids or how digestible the protein is by humans.

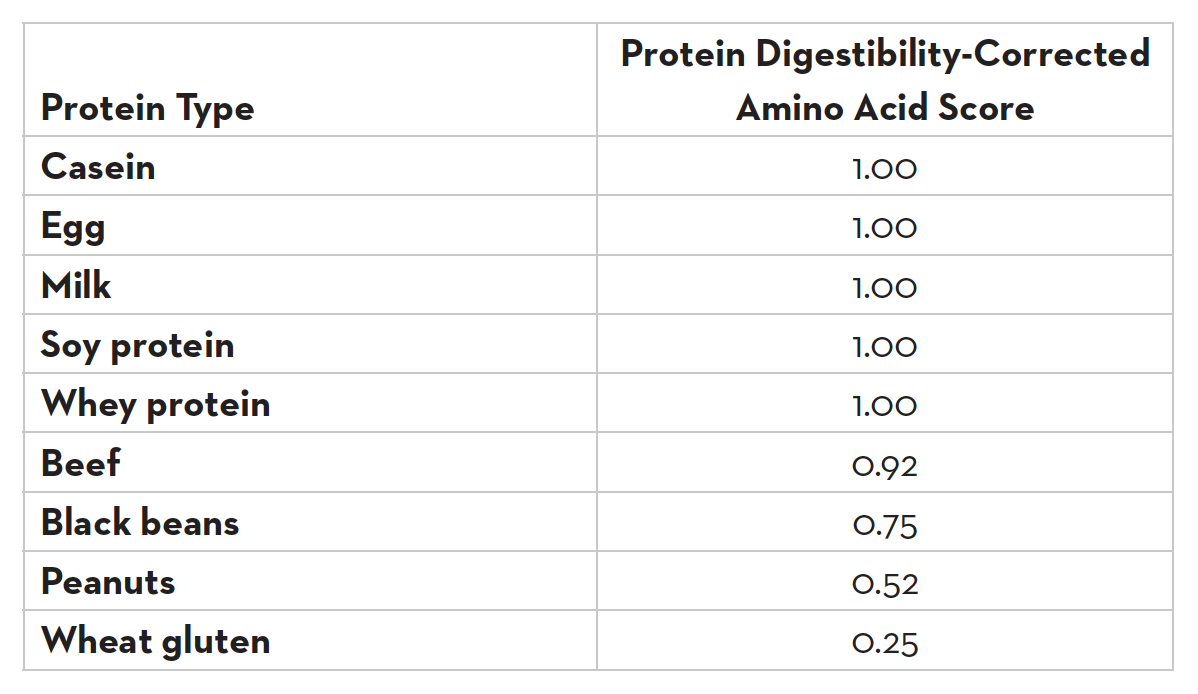

The protein quality in animal products is very different from the protein quality in plants. There are a couple of different ways that researchers and health professionals measure protein quality. The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) was introduced in 1989 by the Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization and has been widely adopted as the preferred method for measuring how proteins best meet human nutrition needs. The table below, with data from the Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, shows beef, casein, eggs, milk, soy, and whey proteins as the highest in nutritional value by PDCAAS.

However, the PDCAAS does not account for antinutritional factors like trypsin inhibitors, lectins, and tannins, which can reduce protein hydrolysis and amino acid absorption from plant-based proteins like soy. Digestibility of plant proteins is also affected by age and the state of the person’s gut. It is widely agreed that animal protein (eggs, milk, meat, fish, and poultry) is the most bioavailable source. Meat-based proteins also have no limiting amino acids, whereas soy is low in the AA methionine and is not considered a “complete” protein.

But it’s no wonder why people are confused.

The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend protein sources from animal and plant sources have been broken down into ounce equivalents. For a healthy adult who consumes 2000 calories per day the recommendation is as follows:

Protein foods: 5 ½ ounces per day

Meat, poultry, eggs: 26 ounces per week

Seafood: 8 ounces per week

Nuts, seeds, soy products: 5 ounces per week

Beans, peas, and legumes are counted as a protein or a vegetable. The recommendation is to eat 1 ½ cups per week of these foods.

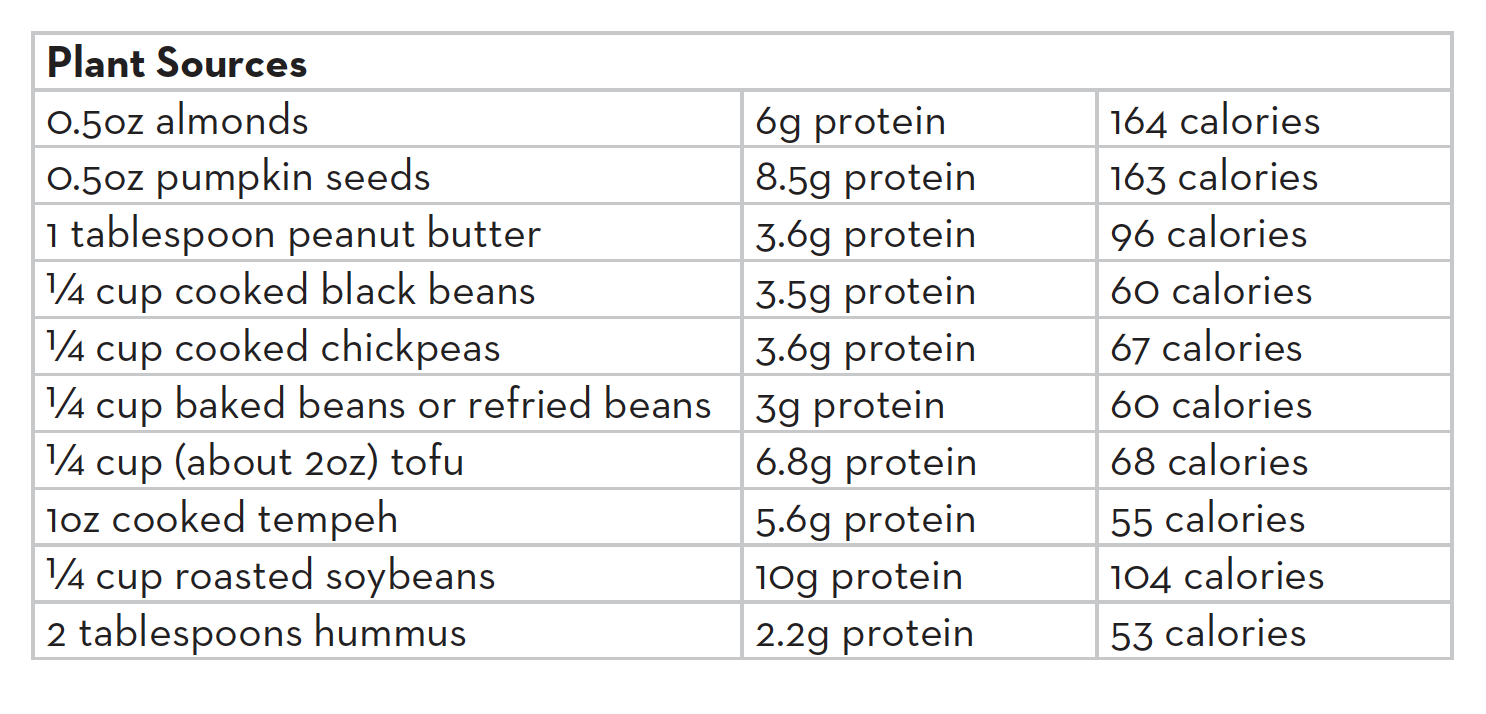

In an effort to simplify how Americans can get their protein, “my plate” recommendations are intended to break down the US Dietary Guidelines into “simple” terms and to be used as a mass teaching tool. The USDA has broken down protein foods into “protein equivalents,” and unfortunately, if one were to follow this advice and try to get one’s protein from plant sources, one would certainly come up short. Here are protein equivalents in the animal-versus-plant category:

If you consumed the recommended amount of protein foods per day, this would total about 40 grams of protein. This is less than the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 56 grams for men and 46 grams for women. It should be noted that the RDA amounts are the minimum level of protein one needs, not the optimal amount, so you would be getting less than the minimum amount of protein if you followed the recommendations, substituting plant-based options for animal-sourced options.

As a dietitian I recommend aiming for at minimum 20 percent of your calories to come from protein, ideally from animal-source proteins. On a 2,000-calorie diet, that means eating 100 grams of protein, or 1.6g of protein per kg of body weight (which is about twice the RDA).

A recent study in the Journal of Nutrition found that the DGA recommendations are not only inadequate in terms of the grams of protein provided, but also in implying that all types of proteins provide the same quality of nutrition.

The study evaluated the anabolic response to different protein food sources in 56 healthy adults over a 3 day period. The subjects consumed one of 7 different protein sources during the three days. Animal foods included: pork loin, eggs, and beef sirloin. The plant-protein foods included: red kidney beans, peanut butter, mixed nuts, and peanut butter. Subjects underwent a metabolic study before and after the three day period to evaluate their protein status.

Researchers found that those that consumed the animal protein sources had a significantly greater net protein balance above baseline, when compared to those who ate the plant-based proteins. The increase in protein balance in the animal group was due to an increase in overall protein synthesis.

The conclusion of this three day study was that the essential amino acid content of the food was correlated to the whole body protein balance. Basically, animal proteins had a greater impact on improving nutritional status. “Ounce equivalents” are simply not equal in terms of metabolic response.

Most of us in western countries are not looking to increase our caloric consumption, yet we want to feel full. Increasing protein is a great way to do this; animal sources are the most desirable sources, in terms of bioavailable protein and other micronutrients.

Those who are food insecure and looking to increase their nutrient intake also benefit from consuming animal protein over plant proteins because animal proteins are better absorbed than plant proteins, and animal proteins contain a broad spectrum of amino acids with more vitamins and minerals than plant proteins.

With the increasing interest in “clean” alternative fats, milks, and plant-based proteins, it’s critical that we acknowledge that they’re not nutritionally equal to the real thing. Almond milk, although it’s a white liquid, pales in nutritional content to actual milk. And when analyzed in labs, it turns out highly processed plant-based burgers are not nutritionally equivalent to real meat.

This does not mean that you should stop eating plants, but it does mean that if you’re relying solely on plant-based proteins, you may not be getting what you think in terms of protein.

Meeting Your Daily Protein Needs

If you want to meet your daily protein needs, how can you do so effectively? Do you need to quit eating plant-based proteins?

Like I mentioned earlier, I recommend aiming for at least 20 percent of your calories to come from protein, ideally from animal-source proteins. On a 2,000-calorie diet, that means eating 100 grams of protein, or 1.6g of protein per kg of body weight (which is about twice the RDA). I’ve seen people have a lot of success at weight loss or muscle building with higher levels of protein too. Protein fills you up, so eating more protein often leads to less overall calorie intake during the day. Plus, animal sources of protein contain high amounts of micronutrients, so you can get the majority of your nutrition simply from animal sourced foods.

However, plant-based proteins are not inherently bad for you. When eaten in combination with other foods, plant-based proteins may provide all the essential amino acids required. But you’ll likely be consuming many more overall calories than someone who gets the majority of their protein from animal sources. So if weight is not an issue for you, you’re great at handling large amounts of carbohydrates, and your digestive system can handle this much fiber, then getting your protein largely from plant sources may not be a problem.

Optimally, a diet should meet the daily nutrient requirements and the job of the DGA should be to recommend optimal, not minimum needs. The source of bioavailability and quality of the protein should be taken into account instead of the current ounce equivalents for a more accurate picture of ideal protein intake.