Where Do Methane Emissions Come From?

Cattle Carbon Cycling

One of the biggest headlines today is that cow burps are ruining the planet.

Methane emissions come from anaerobic breakdown of organic materials (like your composting kitchen scraps), and in the case of food production, some from ruminant digestion. Although there are many contributors to methane production, the villains in the popular story are grazing animals. And we’d like to make the case that getting worried about methane production from any biological process is reductionistic because methane produced via biological process is part of a system, provides no net inputs to the system, and perhaps most importantly, is caused by living organisms! Let’s take a closer look.

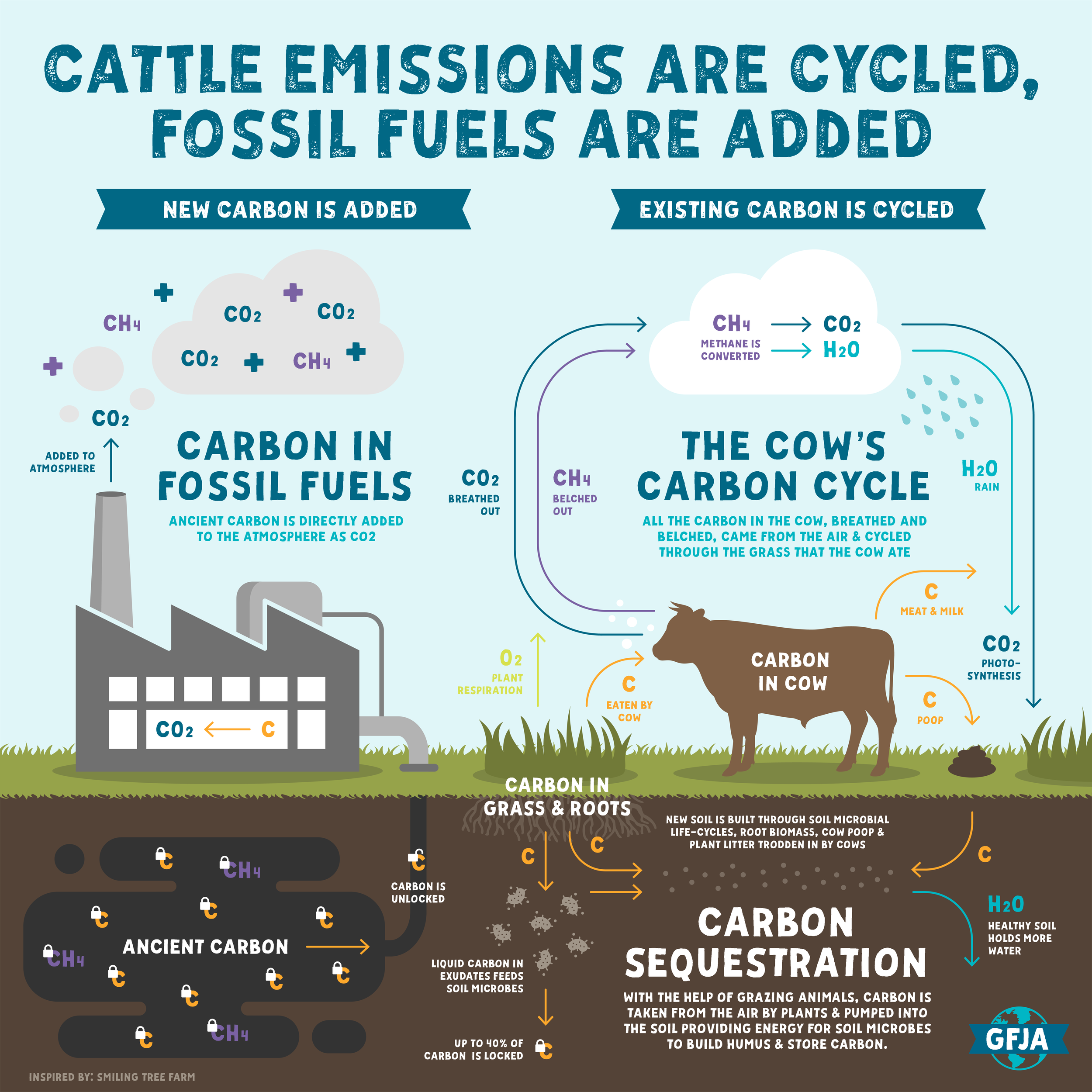

It’s critical to understand that the methane emitted from cattle are part of the natural, or “biogenic” carbon cycle, whereas fossil fuels are not. Fossil fuels come from “ancient” carbon that has been locked underground for millions of years, and when it is extracted, it’s adding new carbon to the atmosphere, which lasts thousands of years.

In the case of cattle, they are transforming existing carbon, in the form of grass and other fibrous materials, into methane as part of their digestive process. Methane is then belched out and after about 10 years, is broken back down into water and carbon dioxide molecules. The CO2 and H2O are cycled back to grow more grass and the cycle continues.

Industrial animal production, with its manure lagoons, is indeed a significant source of methane, but these are largely from the pork, egg, and dairy industries. Beef feedlots generally do not use manure lagoons. And although cattle do burp methane, this is simply a natural byproduct of their digestive process. Some of this breakdown and methane production would happen even if it weren’t inside a bovine digestive tract. Cattle are also upcycling nutrients. They’re converting grass and other plants that are of little nutrient value to humans into high-quality protein while improving the quality of our soil.

Concentrated animal feces from factory farms are a much different environmental issue than scattered cattle poop, urine, and hoof across grasslands in a natural system. In well-managed systems without a lot of antibiotics or drugs given to the animals, large dung beetle populations are re-established. These dung beetles help break down manure, and recent studies found they help to mitigate methane emissions from it. How do they do this? Methane thrives in low-oxygen environments. As they tunnel through manure, dung beetles provide ways for oxygen to circulate, preventing methane formation.

When cows are managed properly they can actually help sequester carbon in the soil. As they walk around and graze, cattle urinate and defecate onto the grass. This natural fertilizer feeds microorganisms in the soil thereby increasing biodiversity and creating healthier soils for plants and animals alike. Moving cattle off of a freshly grazed pasture allows the soil time to absorb this fertilizer while providing the plants time to regrow and maintain their healthy root systems.

Carefully managed grazing also stimulates plant growth and helps ensure that one species of plant cannot overtake a pasture and shade out other forages. The more diverse forages that are in a pasture, the healthier the soils will be.

In contrast, continuous grazing -- a term used to describe situations where cattle are allowed to graze wherever they want as much as they want -- can deplete plant root biomass, increases the bare ground in brittle areas, lowers SOC reserves, and can contribute to soil erosion and compaction, decreasing its water holding capacity. Sediments from eroded soils, both due to overgrazing and poor cropping, emit GHG when organic matter sediments enter anaerobic waterways. Areas like the dead anoxic zone of the Gulf of Mexico, as well the declining numbers of North American pollinators, are examples of what can happen from soil erosion.

Let’s also not forget that prior to the mid-1800s, there were an estimated 30-60 million bison, over 10 million elk, 30 to 40 million Whitetail deer, 10 to 13 million Mule deer, and 35 to 100 million pronghorn and caribou roaming North America. Yet nobody seems to acknowledge this when citing current “devastating” herbivore numbers. According to a paper published in the Journal of Animal Science, in pre-settlement America, methane emissions were about 84% of current emissions.

Ultimately, cattle are a critical link in the relationship between soil, plants, rainfall, and sunshine. Without cattle to keep forages grazed down and to deposit natural fertilizer, many pastures would become stagnant and overtaken by a few species of plants. Well-managed cattle can create healthier soils and more diverse plant life. This leads to better habitat for wildlife and reduces reliance on synthetic inputs like fertilizer. For more discussion about how well-managed cattle improve the ecosystem click here.