Beef is Not a Water Hog

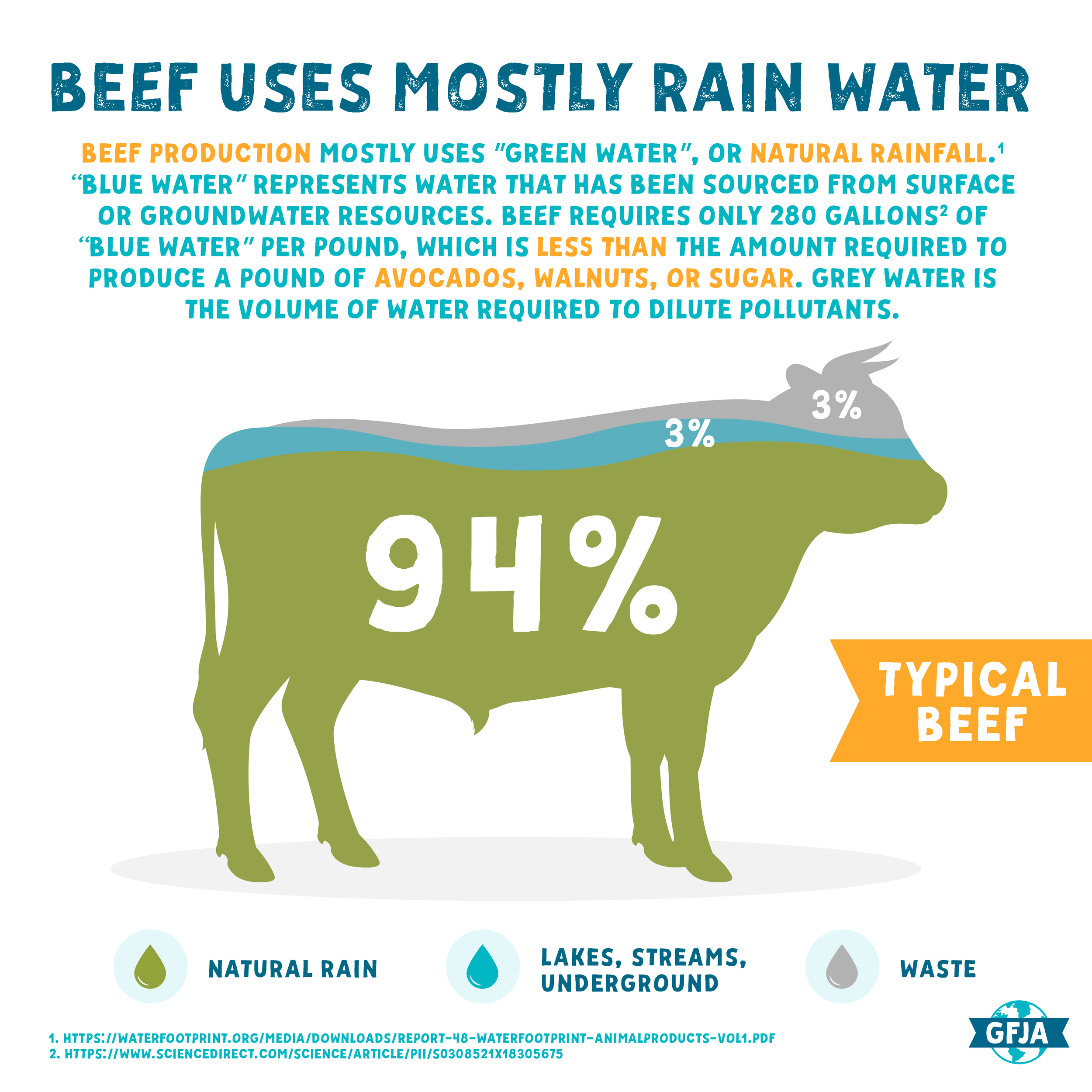

One of the main ways that beef is criticized involves water use. What many of these critiques miss, however, is that 94% of the water “used” to make typical beef and 97% of the water used to make grass-finished beef is naturally occurring rainfall, i.e., rain that would have fallen whether or not that animal was located on that land.

Once you understand how water footprint numbers are calculated, you’ll understand how easily they can be distorted to make beef look like a water hog. Consider these definitions from Waterfootprint.org’s glossary:

Green water is rainfall and naturally occurring precipitation that is temporarily stored in the soil or on top of the soil. It does not runoff into other waterways or infiltrate the soil to reach groundwater storage basins like aquifers.

Blue water is fresh surface or groundwater that can be found in freshwater lakes, rivers, and underground aquifers.

Grey water is freshwater that has been used during some manufacturing or processing practice. It is defined and calculated as the volume of water that is required to dilute pollutants to such an extent that the quality of the water remains above agreed water quality standards.

If you’re measuring meat production looking at green water, this is very different than looking at blue water.

Beef production is able to draw the overwhelming majority of its water needs from natural rainfall because the beef production system begins with a cow-calf operation where herds of cows are raised on pasture and bred to have a calf once a year. Cattle only spend on average the last five months of their lives in a feedlot. This is a massive difference compared to chicken and pork production, which takes place almost entirely inside large-scale confinement houses. In a grass-finished beef operation, the amount of green water used is closer to 98% because the cattle are raised exclusively on pasture.

A recent LCA study showed it takes only 280 gallons to produce a pound of beef. Some estimates put water usage for grass-finished beef between 50 to 100 gallons per pound to produce. By contrast, a pound of rice requires about 410 gallons to produce. Avocados, walnuts, and sugar boast similar water requirements.

Beef-related water calculations also commonly include water used to produce the grain fed to cattle. Livestock feed often requires irrigation, which is considered blue water. But what many people don’t realize is that typical cattle actually consume a very small percent of grain. Only 4% of the 280 gallons required to produce a pound of typical beef is blue water, however. For grass-finished beef, it drops to 3%.

Reducing the discussion around beef’s water consumption to the amount of rainfall that occurs on pastures and the water used in feedlots misses so many key factors about how the animals were managed on that pasture and the benefits they often provide. For more discussion about water use in beef production watch this video by Sandra Postel, the director and founder Global Water Policy Project.

When cattle producers use regenerative practices like rotational grazing, the livestock can actually improve soil health and increase the soil’s water holding capacity. These practices also provide pastures with rest periods that allow any green water that falls during that period to soak into the soil and enhance the re-growing process for pasture plants.

On hard, compacted land, rainfall runs off instead of being absorbed by the soil. If there’s no cover and just exposed topsoil, rain can also wash lots of this great topsoil into nearby rivers (and take with it chemical fertilizers). In a well-managed grazing system, rainfall is absorbed by the soil like a sponge, allowing the roots to have access to the water. This is especially critical in dry environments where there’s little rain to begin with. This benefit can’t be calculated using reductionist thinking. You must look at the entire system.

There are also ecosystem management practices like fencing off ponds, lakes, riverbanks, and other aquatic areas to prevent livestock from having access to these fragile ecosystems or depositing urine and manure into the waterway.

Beef isn’t the water hog we’ve been led to believe.